Mobile healthcare: At home in the long tail?

By Ken Banks

Focussing on where it hurts

Anyone taking more than a cursory glance at recent advances in eHealth – of which mHealth is a subset – will not fail to notice an emerging pattern of centralised projects run by multilateral aid organisations, government ministries or larger NGOs. After all it’s the governments and multinational NGOs who tend to have best access to the funding, technical resources and political will necessary to make these larger-scale projects come off, and it’s the larger, grander projects which tend to dominate the press. Concentrating our efforts at this level tends to overlook the valuable contribution that smaller NGOs and local groups play in delivering services – healthcare among them – to more often than not rural communities. These smaller organisations also need tools, but they are generally disempowered because of a lack of access to the same funding, resources and technical knowledge available to others. The question is, how do we fix this?

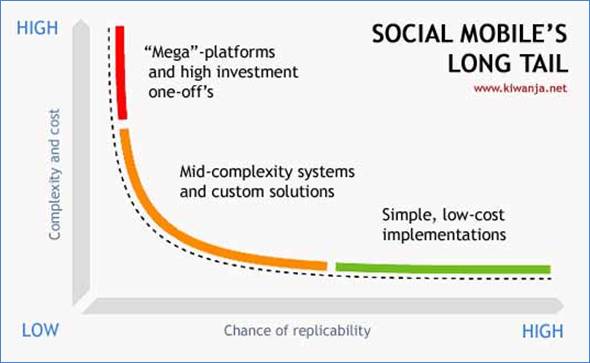

In order to better understand the problem – and how it more specifically relates to mHealth – we need to look more broadly at the mobile applications development space. To do this, I draw on the “long tail” hypothesis, even though it was originally conceived for something entirely different (consumer demographics in business, of all things). Adapting the long tail concept, we end up with a mobile applications space which looks something like this.

We have three categories. Firstly, there are high-end high-cost solutions running SMS services across national or international borders, with little chance of replicability by your average health-focussed grassroots NGO. These are represented by the high part of the curve and generally get the highest amount of press exposure. You’ll almost certainly have heard of these. Then we have lower-cost custom solutions, developed by individual (often mid-level) non-profits to solve a particular problem in a particular country or region, or to run a specific health campaign. These have a slightly better chance of replicability for grassroots NGOs, are represented by the middle section, and generally get a medium to high level of publicity. Depending on where you work, you may have heard of some of these.

Finally, we're left with the simple, low-tech, appropriate technology solutions with the highest opportunity for rapid, hassle-free replicability among grassroots health NGOs, represented along the bottom. These projects generally get the lowest level of publicity, if any, since few have an international profile of any kind. Notoriously hard to communicate with, and with little or no money, it's perhaps no surprise that most of the attention on the long tail is elsewhere. Unless you’re particularly focussed on grassroots NGOs, or are one yourself, it’s unlikely you’ll know much about these (few people do).

When taken in the context of the global health community, the lack of focus on the long tail represents a missed opportunity. Think of it this way. If we consider, for one moment, that for any patient anywhere in the world healthcare is a local, personal experience, thinking about healthcare delivery globally – as most projects seem to – can be misleading. It also brings with it a natural tendency to assume that only the biggest and most visible organisations, and biggest and boldest projects, stand any chance of delivering. It’s this mindset which creates the environment which, in turn, feeds the continuing focus for mobile solutions development at the higher end of the long tail.

Tools – not solutions – for the long tail

Since early 2003 I’ve been focusing my own attention on mobile solutions for NGOs living and working in the long tail. For over 15 years I’ve been working with grassroots non-profits throughout Africa, and have picked up a good understanding of what makes them tick along the way. Interestingly, many of these organisations possess the magic ingredients necessary for successful healthcare delivery in the areas where they work – a local presence, language, cultural understanding and, more often than not, trust. All they generally lack are the tools. The irony is that, when we look closely at some of main reasons for lack of project uptake at the top of the long tail, it’s these very things that they’ve lacked. So, what’s easier – get tools into the hands of the grassroots NGOs, or somehow empower the larger organisations with the local and cultural context they need to succeed?

The evolution of FrontlineSMS

It was a spell of field-based research in South Africa in 2004 which drove me to take the former route, and lead to the development of a text messaging solution for grassroots organisations called FrontlineSMS, the following year. Today, any health NGO – at any point on the long tail, interestingly enough – can have their own standalone, independent messaging hub up and running in no time. A laptop or desktop computer, a mobile phone and cable, and a local SIM card are all they need to be up-and-running in no time. FrontlineSMS is a clear example of an appropriate ICT technology solution for developing countries.

FrontlineSMS in the field: A case study in health education

Based in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rien que la Vérité was born in 2006 when some of the finest musicians in the Congo united to produce a CD of songs speaking against the spread of HIV/AIDS. Since 2006, the Rien que la Vérité platform has produced 14 music videos, a documentary, and an all-day stadium concert. In its present incarnation, Rien que la Vérité is touching the lives of the people of the Congo through their television screens as they follow the lives of a Kinois family on a locally-produced TV drama.

Rien que la Vérité - the TV series - launched nationally on November 30th, 2008 and first implemented FrontlineSMS in the airing of its second episode on December 14th. Each episode broadcast is accompanied by short talk-show segments during which a host introduces music clips, talks to well-known musicians and actors, and interviews representatives from local NGOs and organizations whose message dovetails with a theme introduced in the show.

During the December 14th show, the audience was invited to participate by sending an SMS with the name of their favourite character. The responses were collected using FrontlineSMS. This simple first step allowed Rien que la Vérité to test the software and to begin an exploration of their audience’s perceptions and preferences. As the show continues they plan to introduce more simple polls that will help tailor the show to the audience’s tastes, and give viewers a sense of ownership of the programme. As the SMS initiative moves forward the programme will begin launching a drive to support fan clubs, so that people who watch the show can find each other, meet, and talk about the show and the topics it introduces - a process that will begin to normalize conversation about HIV/AIDS. FrontlineSMS will be used to collect contact information from interested fans, then broadcast messages with times and locations for local club gatherings. They also intend to use FrontlineSMS in their research for measuring the impact the show has on the target audience. Questions will be sent out via SMS to fans before and after each show, measuring any changes in attitude, knowledge, or self-reported practices due to exposure to the show’s messaging.

According to Becky McLaughlin, Marketing Director at Rien que la Vérité, “FrontlineSMS will be a critical tool in our goal to entertain and educate. Like its television format, Rien que la Vérité’s future development must remain grassroots, and FrontlineSMS is an excellent vehicle for this.”

Unlocking the potential of SMS in the long tail

FrontlineSMS has a number of features which make it particularly useful to grassroots organisations such as Rien que la Vérité. Since it runs off the mobile network, there’s no need for the internet, and because it uses a local SIM card FrontlineSMS hubs can be set up quickly and easily in any country, increasing opportunities for other health NGOs to replicate successful projects and share experiences. Recipients can also reply to messages, creating a truly two-way messaging service, something not easily available using web-based messaging services. Each hub can also be used to create its own keywords and surveys, and incoming messages can be exported to other programs such as Microsoft Excel for further analysis, or for sharing. All data is also created and held locally on the laptop or desktop computer – not somewhere on the web – meaning increased security and data protection.

Since launch in 2005, FrontlineSMS has been downloaded by NGOs in over forty countries around the world for use in a wide range of activities, including healthcare lobbying in the USA, to keep students informed of healthcare educational options in Portugal, public health monitoring of communicable diseases in Kenya, a community-based healthcare project in Uganda, the co-ordination of self-help groups in India, blood donation programme co-ordination in Botswana, health alerts to patients in Benin, clinic management and communications in Malawi, and as a reporting tool for avian flu outbreaks across the African continent. Other uses have included election monitoring in Nigeria and the Philippines, and as a tool to help circumvent government reporting restrictions in countries such as Zimbabwe and Pakistan. As a communications hub, and not a solution to any particular problem, FrontlineSMS is an incredibly flexible tool.

Getting and using FrontlineSMS

Setting up and using a FrontlineSMS hub is quick and easy, and requires little technical expertise, a good thing for many grassroots non-profit organisations. The FrontlineSMS website – www.frontlinesms.com – provides detailed instructions, tables of supported phones, details (and a map) of current usage, and a community allowing FrontlineSMS users around the world to connect and interact. After downloading and installing the software via an internet connection or CD, the user attaches a mobile phone or GSM modem which FrontlineSMS will then search for and configure automatically. The user then creates Groups and adds people into those Groups using the ContactManager module (pictured). Any number of Groups can be created, and any number of people added to each Group.

With Groups created, messages can then be sent to each Group, and then messages received from members, facilitating two-way communications via SMS. Surveys can be run, asking people their opinions on health-related matters, or their knowledge of a particular disease or condition, or help-lines set up in which members of the public can text in predetermined keywords – such as HIV, TB or even clinic opening times – and get automated responses determined by the FrontlineSMS administrator. Remote healthcare workers can also subscribe to SMS-groups, and then send messages remotely, through FrontlineSMS, to all other members of their Group. Messages can also be delivered via email, useful if workers are sending health survey information or statistics which needs to be delivered on to a head office. FrontlineSMS is, in essence, a communications platform which, once set up, can be used to distribute any types of message, and to solicit any kind of response in a number of different ways.

Into the future

Many ICT4D conferences set out to encourage shared learning – or more specifically to examine “what does or doesn’t work”. Many invite speakers, often from the developed world, to present papers which demonstrate the transformative effect that mobile technology is having in the developing world, an irony in itself. While additional study does, at times, present new and useful information, there needs to be a concerted effort to move away from discussion and more towards a call to action. Through my own experiences over the past fifteen years – and the last five working in mobile specifically – I have formed my own opinions on what does and doesn’t work, and little has changed in that time. Since the majority of grassroots non-profits in the developing world work in the long tail, it is clear that what we need to be doing is providing appropriate, simple, replicable, affordable tools to enable them to better make use of emerging technology, mobile included.

Although FrontlineSMS may be far from the perfect solution, it does demonstrate what can be achieved by grassroots NGOs – using their own skills and initiative – if they are given the tools they need to operate. These tools don’t need to be highly complex. FrontlineSMS is, after all, the simplest of solutions. If anything, the single most important “what works” lesson is this - if we’re really serious about wanting to empower the grassroots non-profit community, then the long tail is where it needs to be. We don’t need another conference to learn that.

Ken Banks, founder of kiwanja.net, devotes himself to the application of mobile technology for positive social and environmental change in the developing world, and has spent the last 15 years working on projects in Africa. Recently, his research resulted in the development of FrontlineSMS, a field communication system designed to empower grassroots non-profit organisations. Ken graduated from Sussex University with honours in Social Anthropology with Development Studies and is currently working on a number of mobile projects funded by the Hewlett Foundation. Ken was awarded a Reuters Digital Vision Fellowship in 2006, and named a Pop!Tech Social Innovation Fellow in 2008.

Further details of Ken's wider work are available on his website at http://www.kiwanja.net.